Fungibility

It’s hard to get a 1 of 1, but most of the time it’s not needed

Fungibility is one of the most important units of measurement for a manager for their team. Understanding the level of fungibility you need for a specific problem space or role allows you to manage your team optimally. Additionally, properly assessing the fungibility of your team members allows you to gauge how replaceable someone is for your team, and who you need to spend the most mindshare on. Being opinionated on these points allows the manager to optimally allocate their time and budget to hire and retain the best team to fulfill their core purpose.

The framework we can use to help us make these measurements is:

Understand the minimum level of a skillset needed to solve the problem. Most problem spaces don’t need rocket scientists, but do need some baseline level of expertise to work well.

Gauge how fungible someone with the skillset of that expertise is in the job market. This is a question of supply and demand, and understanding both supply/demand ratios and the total size of the supply pool is critical to understand how to navigate the market.

Measure the fungibility of your team members. People are not just a role or a skill, but a complex synthesis of multiple factors. Some people can literally be a 1 of 1 due to the intersection of skillset, experience and character.

A 100x manager wants to make as many roles as fungible as possible while making sure to identify, nurture and retain any non-fungible people they have. By doing this, they achieve a balance where the majority of the team is easy to hire and replace, while they can spend the majority of their mindshare and time on their non-fungible team members.

First, let’s go in a little deeper on what fungibility actually means.

What is Fungibility

Fungibility is the degree something can be exchanged or substituted with other identical items without any loss of value or utility. While fungibility is usually thought of as a binary concept, in reality it is continuous, and there are degrees of fungibility.

Money is an example of something highly fungible, where one dollar and another is exactly the same - as the holder of money you don’t care which specific dollar you have, and you are indifferent to exchange your dollar with another one.

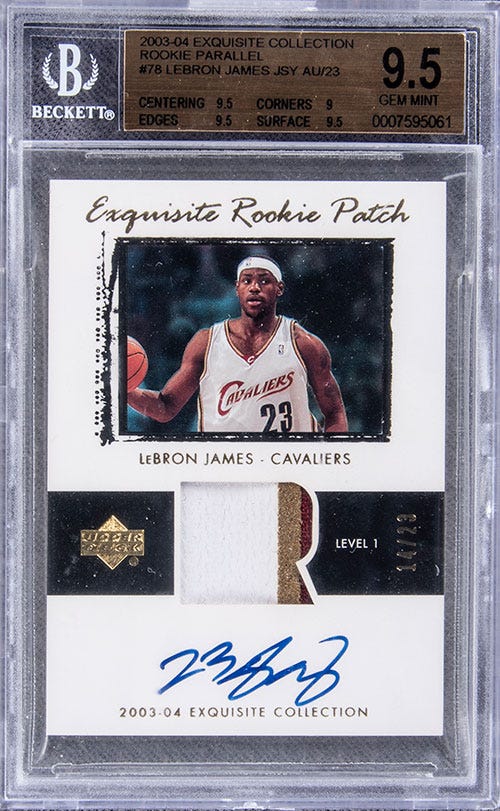

High-end collectible art is an example of something non-fungible, where no two pieces are the same, and as the holder of a piece of artwork, you generally will have a strong preference for that specific piece.

A house is an example of a semi-fungible good. While no two houses are exactly the same, a home buyer will generally accept a set of homes as long as they match some criteria (e.g. location, number of bed/bathrooms, etc.), and within the criteria the houses will look more fungible.

This is a useful framing to evaluate the true supply and demand of a thing. As a user of a thing, you prefer it to be more fungible. As an investor or collector of a thing, you would prefer to be semi-fungible, and as the thing itself, you would prefer to be non-fungible.

Fungibility of the Role

As a manager, you are effectively a user of skills, and you will prefer your roles to be more fungible if possible, all else held equal. However, for most problem spaces, there is a minimum expertise that you demand that is much higher than the minimum expertise offered in the market. Properly determining what level of fungibility you need and managing this tension well will help you build optimal teams for achieving your goals.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to 100x Manager to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.